Darlington Works No. 2055 was constructed in November 1948 with boiler No. 3924. The first record of it was on the 20th. It was one of five turned out that month, three from Darlington and two from Doncaster. It was painted in LNER apple green with white and black lining with ‘BRITISH RAILWAYS’ on the tender. Numbers and letters were in old gold. As with all Darlington examples countersunk rivets were used to give a smooth finish to the cabsides and tender.

Entering traffic from Copley Hill (COP) on 26th November it was to be one of five A1s initially allocated there. It was noted at Doncaster on 23rd December but its first recorded working was on the up ‘Yorkshire Pullman’ on New Year’s Day 1949. It worked between Leeds and the capital both on ordinary passenger trains and named expresses like bringing ‘The Queen of Scots’ into Leeds on 28th May and taking the 11:30hrs down ‘Queen of Scots from King’s Cross on 2nd July.

A transfer to King’s Cross shed (34A) took place in May 1950. Naming and repainting into BR blue with black and white lining and the early BR emblem on the tender took place that December following a heavy intermediate repair. Though one of the earlier A1s built, No. 60136 was one of four named that month to join 28 others already with names. It was well down the class for appearance in blue. With 41 already that colour No. 60136 was one of two repainted in December. Its name Alcazar was one of the thirteen racehorse names bestowed on A1s. Alcazar had won the St. Leger in 1936, alcazar is a type of castle built for kings in Spain and Portugal and derives from an Arabic word. On 2nd February 1951 No. 60136 was seen at Darlington with the thirteen coach down ‘Flying Scotsman’.

A transfer to Grantham (35B) was made in January 1952 along with eight other A1s. A repaint into BR green with orange and black lining was done in January 1952 as one of four to join the 18 in green already. Following its first general overhaul in April 1953 which included fitting boiler No. 10599, workings generally seemed to range between the capital and Newcastle but one occasion of note was the locomotive’s involvement in taking HM the Queen south from Aberdeen on 18th May 1953, a working which was unusual in that involved attaching three royal coaches to the up ‘Aberdonian’ thus increasing the weight of an already heavy train; No. 60157 Great Eastern worked the section from York to Peterborough whence No. 60136 Alcazar took it on to King’s Cross. During a period that was interrupted by a further ‘General’ over Christmas 1955 (boiler No. 10596 fitted), a number of times in 1955 and 1956 Alcazar brought the down ‘Flying Scotsman’ into Newcastle though on 18th December 1956 it departed King’s Cross with the down 10:00hrs ‘Flying Scotsman’. Another named train hauled by No. 60136 was ‘The Northumbrian’, the 10:00hrs up train from Newcastle on 23rd June then the 12:20hrs down train from King’s Cross on 25th September. When it pulled the down afternoon ‘Talisman’ on 9th September 1957 its eight coach rake included the ex ‘Coronation’ twin-set. In October it was a regular performer on the 10:20hrs King’s Cross-Leeds. Many times that year and in 1957, departures from London on ordinary passenger trains were noted, the most common being the 10:20hrs to Leeds, the 20:20hrs for Edinburgh and the 05:50hrs to Grantham. After earlier workings in the day on 5th and 6th December 1956 it hauled the additional 19:30hrs King’s Cross-Grantham.

No. 60136 Alcazar on a down train approaching New Barnet Station in 1957 – Robin Gibson

Acazar at ‘Top Shed’ on 30th April 1957 – PeterTownend

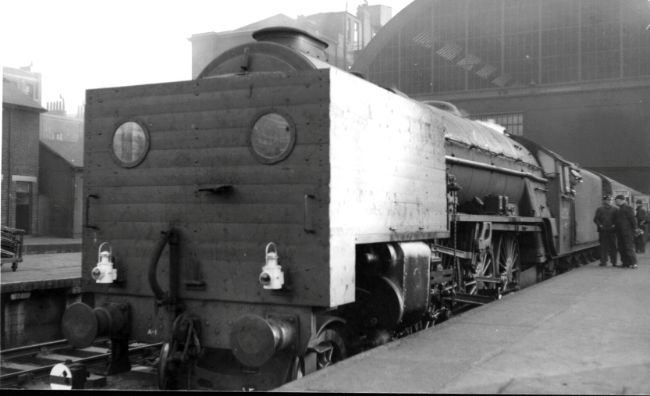

On 7th April 1957 Alcazar transferred back to King’s Cross shed. The locomotive re-visited Doncaster for another general overhaul during June 1957, receiving boiler No. 29863 in the process and the later BR crest was applied to the tender, the locomotive probably losing its Stones generator and electric lighting at the same time. It still worked as far as the North East with a sighting on an up passenger at Usworth near Chester-le-Street on 8th September. This locomotive had a reputation for particularly bad riding so it was sent to Doncaster works in November where it was found that the middle cylinder had been set with no expansion allowance and an A4 type bogie was fitted. Indicator shrouds were fitted to the front of the engine to monitor performance on King’s Cross-Newcastle trains and the riding was much better. Each day from 25th – 29th November 25th it worked the 07:43hrs York-King’s Cross and 14:10hrs return. A trip to Scotland came in February 1957 as it was seen on the up ‘Flying Scotsman’ from Edinburgh to Newcastle on the 11th.

No. 60136 ‘Light Engine’ at Doncaster 10th April 1961 – Mike Mountford

6th April 1958 marked a transfer to Doncaster shed (36A) but it went back to King’s Cross shed on 3rd August. On 5th April 1959 No. 60136 was reallocated back to Doncaster with four other A1s, returning to ‘The Plant’ in May for another general overhaul, leaving with boiler No. 29861 fitted. Notable sightings were the up ‘Master Cutler’ from Retford to King’s Cross on 13th December 1960 and the up ‘Tees-Tyne Pullman’ descending Holloway bank on 9th September 1961, a year interrupted by its final visit to Doncaster for a ‘General’ which include the fitting of its final boiler, No. 29784, a Thompson Diagram 117 boiler with thicker barrel plates and the round dome further forward. More mundane was the 14:05hrs Leeds-Doncaster local of 30th June 1961. Between that September and July 1962 No. 60136 was serviced a number of times on Gateshead shed. Leeds- King’s Cross trains were worked too as on 24th August and the opposite direction also. The afternoon ‘Talisman’ was taken from Doncaster to King’s Cross on 30th May. On 30th August Alcazar was the standby engine seen stationed just south of Doncaster station at 10:45hrs but was in full cry though when seen picking up water at speed from Langley troughs with its train of ex-LNER coaches and BR Mk Is on 9th September. Four times in September and October No. 60136’s diagram was the 1A12 Newcastle-Tyne Commission Quay passenger (though the A1 would come off at Newcastle) to return on the 3E22 up fish train. On 10th January 1963 Alcazar was on the 12:40hrs King’s Cross-Doncaster passenger. The last workings noted were the 1A39 09:30hrs ex-Glasgow to King’s Cross from Newcastle on 6th April 1963, the same train on the 9th even though it was booked for A4 haulage, then an up special into King’s Cross on 11th May.

An undated image of Alcazar in late, work-stained condition near Grantham – Bill Reed

Six boilers were carried by No. 60136 instead of the class average of seven. Alcazar was the eighth A1 withdrawn when its turn came on 22nd May 1963. It lasted 14 years and 6 months, 8½ months less than the A1 average. Unlike others it did not languish long and a week later it was taken into Doncaster Works for cutting up.

This history was compiled by Phil Champion based on the RCTS book “Locomotives of the LNER Part 2A”, a database supplied by Tommy Knox of the Gresley Society, “The Pioneer” (A1 Steam Locomotive Trust) and various published photographs. Revised and updated by Graham Langer, June 2020.

INDICATING ALCAZAR by Bill Marley

Bill Marley was a member of the dynamometer car staff when No. 60136 Alcazar was tested between Doncaster and King’s Cross and had the rare experience of riding on the front end of a steam engine inside the indicator shelter. The following account is from Peter Townend’s book ‘LNER Pacifics remembered’ and is reproduced with Peter’s permission.

The tests were of four days duration from 26th – 29th November 1957 on a Doncaster rostered passenger train to King’s Cross and back. The running inspector was an irrepressible character called George Tasker who had a tough uncompromising appearance but a dry wit. It was decided to use the Crosby Marine Type Indicators for measuring the steam distribution at the respective ends of each cylinder. Only two cylinders could be indicated simultaneously but all three were done during the duration of the tests. It was necessary to have a wind shield on the front of the locomotive for the protection of the test staff. This was a substantial wooden structure made of boards approximately an inch thick battened together and arranged to form a box around the front of the engine. It was securely anchored to the footplate and painted black. Two strong glass portholes in brass frames were fitted into the front panel for the benefit of the test staff. Inside the box were two raised platforms, one fitted to each side for the indicator operators to lie along to take the diagrams. A colleague suggested it would be nice to have padded boards and this was arranged together with a covering of Rexine. The front and rear covers of each cylinder were drilled and tapped and brass connections fitted from which lagged copper pipes were taken to the indicators.

Indicator diagrams were taken under controlled conditions of full regulator and a nominal steam pressure over a range of selected valve cut offs. There was two-way communication between the cab and dynamometer car and when conditions were right the front-end staff were alerted by means of an alarm bell. This was their cue to take the diagrams and upon completion reload the drums in readiness for the next test.

At the time riding in the box was looked upon as a novelty compared to routine testing and was something very few people had the opportunity to do. The riding characteristics were possibly similar to those experienced in the cab but generally it was a controlled lateral oscillation but with hard vertical vibrations from the track. Turbulence of the air created problems. When travelling at speed the displaced air would tear around the back edge of the box then forward along to the smokebox to finally whip up over the smokebox door. Anything loose such as logging sheets or indicator cards could be swept away and lost. It was for this reason that the indicator cards were kept in small wooden boxes with heavy steel plates fastened to the lids to keep them anchored. The upward air streams had one advantage, however, as it kept the operators dry when travelling at speed through rain.

Alcazar at King’s Cross awaiting the 14:20hrs departure to Leeds on 27th March 1957 with the indicator shelter in place. - J F Aylard courtesy of The Stephenson Photograph Collection

On one occasion when leaving King’s Cross station the conditions were just right for taking a diagram at full regulator and long cut-off. We were in position taking diagrams when we went under a signal gantry. The speed was low and the gantry sufficiently wide to deflect the steam blasting from the chimney back into the wooden box. It left us gasping for air and our faces the colour of lobsters. On another occasion, when speeding downhill from Stoke to Grantham during one of our slack periods, my colleagues and I stood up and looked over the top of our black box. It so happened that a gang of platelayers were working on an adjacent track ahead and as we approached the supervisor took off his bowler hat and solemnly placed it on his chest giving the impression as if we were a cortege passing by.

It was on one of these downhill runs that our inimitable Locomotive Inspector decided to give the front-end staff a ride to remember. He got the driver to attain a high maximum speed all the way which inevitable meant in some cases exceeding the usual 90mph. The results were disastrous, the vibrations causing all our pipe nuts to work loose and even our alarm bell lost its bell and clanger. By the time we ran into the next station steam was blowing from the joints of all our indicator pipes. The Stationmaster was on the platform as we stopped and was quite cheerful as we were early but his mood changed and he became quite agitated when Inspector Tasker insisted that all the pipe connections would have to be tightened and communication equipment made good before he could allow the train to proceed. This caused a little delay but ensured safe conditions for the rest of the journey.

The results of the tests showed that generally the distribution of steam to the front and back of the cylinders was reasonably similar for the outside but on the middle cylinder it was found that much more work was being done on the back stroke than on the front of the piston. On this class of locomotive, the middle cylinder is set forward from the outside cylinders and the back edge of the middle casting corresponded to the front edge of the outside cylinders. It was suspected that because of the configuration of the cylinders the frame and middle cylinder were expanding forward when hot. By tramelling from a datum point to the centre line of the outside cylinders and to the centre of the middle cylinder it was found that there was no expansion to the outside cylinder but a sixteenth of an inch to the middle cylinder. When the valves were set, half this was allowed for expansion but in light of these readings it was recommended that although it should still be the case for the outside cylinders, no expansion allowance should be made when setting the valves on the inside cylinder.

INDICATING ALCAZAR by Tom Greaves

The editor was fortunate enough to be able to interview Tom Greaves who was also present during the indication trials of Alcazar and shared the shelter with Bill Marley among others. Here are some of his recollections.

I was based at Hertford East in 1957 when the question of testing and indicating No. 60136 Alcazar arose. The Peppercorn A1s had a bit of a reputation for “wagging their tails” and the locomotive had been fitted with a Gresley type bogie so it was decided to make it the subject of a series of road trials on the East Coast Main Line, mainly between King’s Cross and Grantham where it came off the train to be replaced by another Pacific. We are aware of the tendency for the class to be a bit boisterous and a short-term solution was to tighten the tender drawbar up to act as a damper, if a locomotive started to get lively again we’d give it a couple more turns! This treatment did, however, cause additional wear the leading tender axle bearings, at least on those fitted with plain bearings.

Fitting the indicator shelter involved removing the locomotive’s smoke deflectors and I think the upper sides of it were braced back to the deflector brackets. Among the indication team was Inspector George Harland and he instructed the crew to work the locomotive with a full regulator as much as possible during the trial. Compared to what is possible these days the marine-type indicators we used were fairly crude but assessment of the results allowed a reasonably accurate interpretation of the data generated. The paper rolls were more than sufficient to record an entire run, changing them would have been a challenge while on the road and you certainly didn’t want them blowing round inside the shelter. I remember that the top lamp bracket could only be reached from inside the shelter, although a step was provided on the front of it you wouldn’t have been able to reach it – needless to say, you also had to keep your backside away from the smokebox door! It was a tremendous experience and also gave us the opportunity for some pranks, such as the occasion we ran into Grantham with two of us resting our chins on the top of the front of the shelter, like a pair of heads on spikes - apparently a lady on the platform fainted!

I loved the A1s (even though I am a Stanier man at heart) and I rated them better than any of the Gresley Pacifics. They steamed freely (in fact I preferred to fire them rather than driving) and could easily achieve 95mph although you had to fight for every additional mile per hour over that speed. As long as you kept the firing light and made sure the back corners were filled up they’d make plenty of steam, as I’d say to the driver, “I’ll make it, you use it!”. Great locomotives!