Serious incidents involving Peppercorn A1s are remarkable for their scarcity, especially given the enormous mileages the locomotives accumulated during their short careers. There were four accidents which resulted in serious damage to the locomotive concerned, none of which led to a loss of life. Only one involved a passenger train and therefore no official reports were filed concerning the others, making research on this subject quite a challenge.

Collision at Lincoln 25th October 1949 – No. 60123 (later H.A.Ivatt)

No. 60123 may have been the unluckiest of the Peppercorn A1s, coming to grief twice during its career. In the early hours of Tuesday 25th October 1949, when the locomotive was only a few months old, it was involved in a collision with a goods train at Lincoln. It was still dark and conditions were foggy, No. 60123 (still unnamed) was working a fast goods train, the 00:10hrs King’s Cross to Doncaster, on the Lincoln avoiding line (the ‘High Line’) under permissive block rules, in other words, proceeding on sight. The train would not have normally taken the loop line but had been diverted because of a broken rail at Claypole, which may have played some part in the ensuing drama. On the skew bridge over the Coulson Road, No. 60123 ran into the back of a slow-moving goods train, shattering the brake van before turning over on its side down the 30’ embankment on which the line runs at that point. Both the crew of the A1 and the three men in the brake van had lucky escapes and no-one was seriously injured. Both Peterborough men, driver of No. 60123, C. J. Basker, sustained a cut to his head and his mate, John Negus, suffered a cut eyebrow, whilst the guard, Fred Hunter, a Lincoln man, had a shoulder injury which required a trip to hospital for an X-ray and treatment. Travelling in the van with Hunter were a spare crew, driver F. Willis of Doncaster and guard George Sharrock, who received only minor injuries which were dealt with in Lincoln County Hospital.

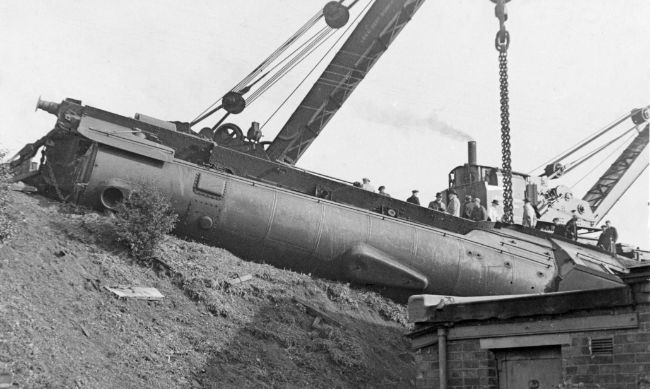

The upturned locomotive lying on the embankment side near Coulson Road, Lincoln - Stephen Williams

It is remarkable that nobody in the brake van was badly injured since No. 60123 dashed it to pieces before the van’s wrecked stove then set what was left of the vehicle on fire! The remains of the van ended up at the bottom of the embankment with the A1 nearly on top of it! Local people were roused from their sleep by the sound of roaring steam and called the local fire brigade who extinguished the burning brake van. The wreckage completely blocked both running lines and breakdown gangs from Peterborough, Lincoln, Colwick and Grimsby were summoned. Heavy rain made recovery operations difficult, preparatory work included removing the damaged rolling stock, re-laying the track and shoring up the embankment to provide a safe position for the crane outriggers. The loop line was back in operation the next day with trains proceeding with “extreme caution” as plans were finalised for lifting the locomotive on the Sunday of that week. Cranes from Peterborough and Colwick attended, the team including District Officers and Shed Masters and a young Allan Garraway who recorded events in his memoirs.

The locomotive lies stricken under smashed wagons - Lincolnshire Echo

“The first job was to drag the tender up the bank, lay it on its side at the top, roll it over and put it on the track, a simple operation which took just over an hour.” recorded Garraway. In fact, the tender was lifted from its resting place inverted, chains and hooks being passed through the frames. “The two cranes were then so positioned that they could both drag the back end of the engine up the embankment. Once that was on top of the bank, it was parallel to the track and the cranes were repositioned so that the engine could be rolled over onto its wheels. It was then a simple rerailing job, which was completed just as it was getting dark.” The cranes were working at their limit, a process made all the more difficult by the lack of width in the formation at the top of the bank which required anchor foundations in addition to track clamps. The locomotive had been prepared for the lift by the removal of its ashpan and firedoor and most of the cab fittings and the subsequent preparation of an attachment through the firehole to which the cranes could be fastened. A week later the Grimsby crane and gang visited the site clear up the brake van and any other remaining debris.

The cranes lift the tender (upside down) onto the tracks - Kevin Hoggett

No. 60123’s tender after being righted by the Peterborough Loco Dept. breakdown crane - Stephen Willaims

With tender out of the way, attention turns to No. 60123 - Kevin Hoggett

No. 60123 was delivered to Doncaster on 7th November for a ‘Light Casual Repair’ (!) followed by repainting into BR express blue before its release in December.

In Top Link, Issue No.3, Spring 2002, we carried the following letter from Covenantor Stephen Williams which is worth re-printing to add some further detail to the story above. Stephen has very kindly scanned the images again which we can now reproduce in a much better format.

“You may be interested in the following information for your A1 Datafile. It concerns an accident involving an almost brand-new A1 Class locomotive at Lincoln in October1949.

My grandparents lived in Coulson Road, Lincoln for a period after the Second World War. Beyond the back garden of their terraced house ran the Lincoln Avoiding Line, known to local railway enthusiasts as the “High Line” because it ran on an embankment in a roughly west – east direction across the south side of the City from Pyewipe Junction to Greetwell West junction. Part of the Great Northern & Great Eastern Joint Line, it enabled goods trains to avoid the notorious bottleneck at High Street crossing near Lincoln Central Station.

My father recently gave me two black & white photographs (see attached) of a mishap involving an A1 on the High Line in October 1949. One picture shows the locomotive lying on the embankment side near Coulson Road, the other one shows the damaged tender after being righted by the Peterborough Loco Depot breakdown crane.

The locomotive was then unnamed, and had a double chimney of the earlier, unlipped variety. The tender is in light livery (presumably apple green) with ‘BRITISH RAILWAYS’ lettering. The first three numbers (601) on the front numberplate can be identified from the upper photograph using a magnifying glass, but the fourth and fifth numbers are unclear. The origin of the photographs is unknown. Incidentally, I was only one year old at the time, and have no personal recollection of the accident!

Yours faithfully, Stephen Williams. (Trust Member No. 274)”

Derailment at Tollerton 5th June 1950 – No. 60153 (later Flamboyant)

The headlines in the newspapers on 6th June 1950 could so easily have read, “Flying Scotsman wrecked!” had that train, by a slim margin, avoided the fate that was to befall the train following it on the East Coast Main Line. There is no record of which locomotive was hauling the up ‘Flying Scotsman’ that morning but we know all too well that the engine pulling the subsequent service was Peppercorn class A1 No. 60153 (later Flamboyant) and that it came to grief in a spectacular fashion.

The scene – Tollerton station is about ten miles north of York on the East Coast Main Line and at this point the line is a four-track section, almost level and dead straight, running north to south. Tollerton signal box is in the middle of a section between Alne and Beningbrough boxes and on the morning of the accident it was switched out and its colour light signals were operating automatically, the lines being continuously track-circuited. During a period described as a “heatwave”, the morning was already warm with the thermometer climbing into the high 80s after a week of very hot weather, the sky was clear and visibility good.

‘The Flying Scotsman’ – Into this scene came the 10:00hrs Edinburgh to King’s Cross, up ‘Flying Scotsman’ consisting of thirteen vehicles and travelling at about 65mph. After passing Tollerton driver W. Etrington noticed that a brake application had been made and, after initially thinking the communication cord had been pulled, he quickly realised that it must be the guard and made a full brake application. Once the train had come to a stand, at about 14:20hrs, Etrington looked back to see the guard, G. Olney, examining the rear coaches of the train and asked his fireman, T. Atkinson, to go back to find out what was amiss. Olney mentioned to Atkinson that the brake coach had given a lurch and its cell box was broken and that the third vehicle from his end of the train had its dynamo belt adrift, possibly through hitting some obstruction on the track. Having cut the remains of the belt free and shown it to Atkinson, Olney walked with him to the locomotive, the fireman continuing to the next signal to ‘phone control and ask that the coaches be examined at York (not a booked stop for this service). It appears that on his way back to his van, Olney told a platelayer what had happened and the latter, who had a bicycle, said he would go back and inspect the track. The train restarted at about 14:27hrs and proceeded to York.

On arrival at York, carriage and wagon foreman Appleby was ready to examine the rear vehicles of the ‘Scotsman’ and Olney told him that he “had been violently thrown about and it seemed as if he had been off the road”. Appleby got the impression that something quite abnormal had occurred and went to look at the coaches. The bogie solebars of the rear brake van were seriously distorted and there was sufficient damage to the rear two vehicles to warrant removing them from the train as unsafe to run. It was Appleby’s opinion, and that of the chief foreman, J. Gladders, that the affected vehicles had been subject to very violent oscillation.

The signalmen – Relief signalman B. Lacey was on duty in Alne signal box when the up ‘Flying Scotsman’ passed at 14:07hrs, shortly afterwards he was informed by his colleague in Beningbrough box that the train had stopped in section and therefore he placed the signal immediately behind it at danger and the others at caution. At 14:24hrs he was offered the 12:15hrs service by Pilmoor South box on the main line but on informing Beningbrough was told that the ‘Scotsman’ was on the move again. However, to be sure, he contacted Control to ask whether the express should be turned onto the slow line but was told to send it along the main line. He therefore cleared the signals and the 12:15hrs express which had slowed to about 10–12mph, passed his box at about 14:29hrs.

Lacey’s colleague in Beningbrough box, E. Kettlewell, was offered the up ‘Flying Scotsman’ at 14:06hrs and accepted it. By 14:13hrs he realised that it was overdue and noticed two of his track circuits were occupied and remained so. He therefore asked Lacey to hold subsequent trains with a view to diverting them onto the slow lines, however, at 14:21hrs the track circuits cleared and the train was obviously on the move again passing his box at 14:26hrs; two minutes later he was offered the 12:15hrs express and accepted it on the fast line. At 14:33hrs Kettlewell received a ‘phone call from a platelayer from a signal (U6) stating that the guard of the ‘Scotsman’ had reported that he thought his train had hit an obstruction and that he, the platelayer, was relaying this information to Kettlewell; a minute later Kettlewell received “Obstruction Danger” on the block bell.

No. 60153 and the 12:15 Express from Newcastle – The driver of the A1, William Streeton of York, had joined his present link in February 1949 and had covered this section of line a number of times shortly before this June day. In his evidence he recalled seeing signal U12 at Alne showing a double-yellow aspect so he shut off steam and immediately reduced speed. The next automatic signal, U11, was showing a single yellow but beyond this, signal U11B, a controlled signal, cleared to green so he put on steam again, passing the latter signal at about 25mph. The train’s speed had increased to about 35mph as it passed Tollerton station but immediately after passing under the bridge at the north end of the station he saw that the track ahead was distorted, just 60 – 80 yards ahead of the locomotive, the rails describing an ‘S’ shape, first to the left and then to the right. Streeton at once made a full brake application but this had little time to arrest the train’s progress before it was derailed to the left. Streeton’s fireman, Brian Carr, also from York, realised something was up as soon as the brake went in and, looking ahead, saw that the track was kinked and felt the locomotive go over to the left. The train’s guard, F. Hobman, noticed the brake application just before he was thrown to the floor of his van and was unable to regain his feet until the train had come to a stand.

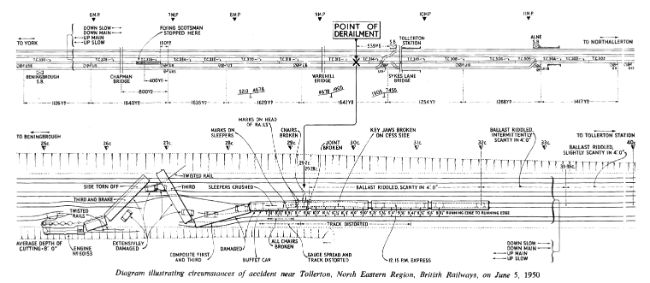

A diagram of the accident taken from the Ministry of Transport Report. – British Railways courtesy of NERA

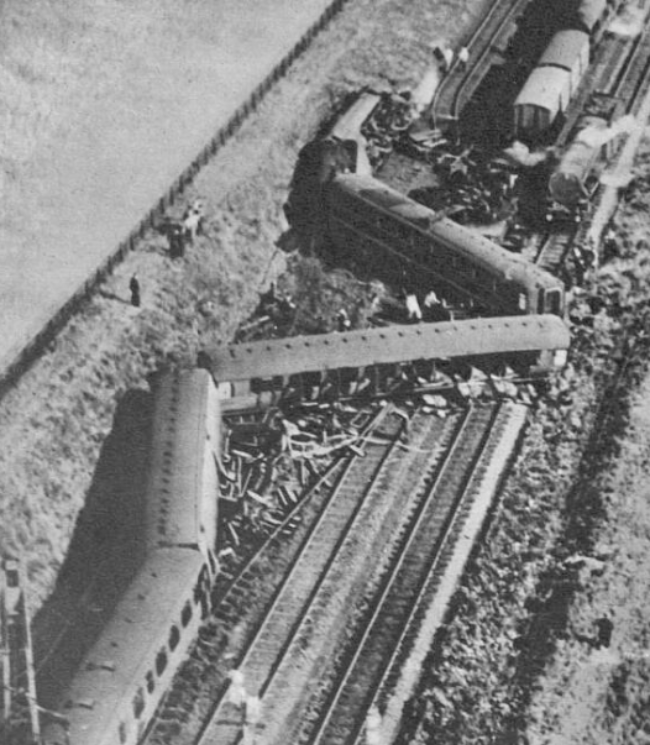

An arial photograph of the accident before recovery work commenced, taken by a Yorkshire Post reporter on the day of the accident. – Yorkshire Post

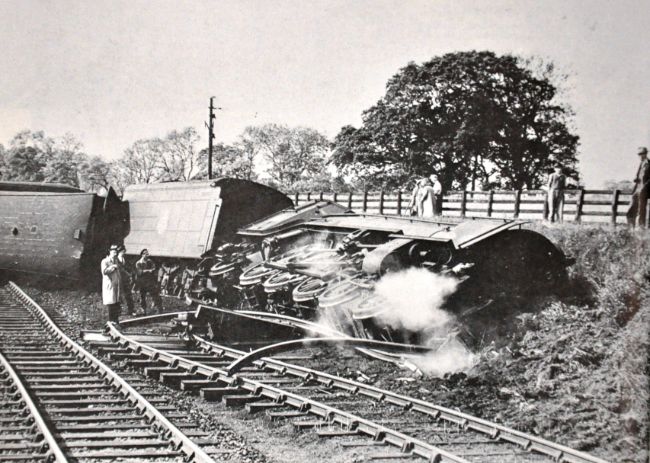

Thankfully the 12:15 Express had not been travelling at its usual speed at this point, normally about 65mph, and the brake application may have made some further reduction before the train came to grief. The A1 was completely derailed and fell onto its left-hand side, coming to rest against the side of a low cutting at an angle of about 45 degrees having cut through the adjacent slow line in the process. Built at Doncaster and outshopped in BR express passenger blue livery on 26th August 1949, No. 60153 was one of the roller-bearing fitted members of the class, by the time of the accident it had accumulated about 66,000 miles and was in tip-top condition and sustained surprisingly little damage. Consisting of seven coaches, the all-up weight of the train was some 400 tons (of Gresley teak stock) and the leading coaches jack-knifed across all four lines; the first coach, a corridor brake third with a welded underframe, turned on its side, losing much of the right-hand (corridor) side and the body separating from the underframe before it ended up across all four tracks with one end crushed against the locomotive’s tender. The second (third class) corridor coach, derailed to the right, also ending up across all four lines and, again, lost most of its right-hand side although in this case it was the compartment side that was torn off, whilst the third vehicle, a Gresley corridor composite, derailed to the left, ending up across the slow line. The fourth coach, a restaurant car, and the rest of the train remained upright and more-or-less in line and sustained mainly superficial damage compared to the three leading vehicles.

No. 60153 rests against the cutting side after crossing the slow line and toppling over. – R. Denny/NERA

Another photo from a different angle. – A. B. Compton/Ken Hoole collection

Extricating himself from his stricken locomotive, driver Streeton, despite his injuries, set about protecting the Down lines with detonators and his fireman tried ‘phoning the signal box without success whilst the station master at Tollerton, realising an accident had occurred, opened the locked signal box and sent the “Obstruction Danger” code to the neighbouring boxes. The driver and fireman of No. 60153 and nine passengers were injured in the crash (one badly enough to require a stretcher) and were removed by ambulance to a hospital in York but none were detained. The remaining 100 or so passengers were conveyed by bus to York and the clearing up operation commenced at once. Needless to say there was considerable disruption to East Coast Main Line services with passenger trains diverted via Starbeck and Senderby and freight traffic held. Breakdown cranes and crews attended from Darlington and York, the Down slow line was re-opened for traffic 23:40hrs the same night, the Up and Down main lines by 08:00hrs the next morning and the Up slow by midday on 6th June after a total interruption of just over 26 hours. No. 60153 was sent to Doncaster for a ‘Heavy Casual’ repair, the only consolation being that following this work the locomotive left ‘The Plant’ bearing the name Flamboyant.

Recovery operations looking south. The steam crane is lifting the third coach of the train, its arc reduced by the automatic colour light signals (mentioned in the text). - NERA

Speaking to The Yorkshire Post after the accident, driver Streeton said, “If there is a lucky man in this country tonight, I am that fellow, and that must also apply to my fireman and the passengers in the train. When I saw the bent line only a short distance away, there was nothing I could do except apply the vacuum brakes. After I put the brakes on it was simply a matter of waiting for the best or the worst.”

The enquiry and its conclusions – It is clear from the above that track distortion was to blame for the damage to ‘The Flying Scotsman’ and the derailment of the 12:15 Express. Colonel D. McMullen, Inspecting Officer for the Ministry of Railways headed the subsequent enquiry. Having gone through the statements and evidence provided his conclusions were as follows. It was apparent that there had been a failure of the expansion gaps between the 60’ length rails, had the rails been able to take up the slack in these joints the track should have been well-able to cope with the high temperatures present during that week. In normal conditions the gap in these rail joints will vary between 1/2” (at 50 – 75°F) and closed (at 100°F) and the recorded rail temperature that day was 104°F, within normal parameters for well-maintained expansion joints. Despite the issue of “hot weather instructions” there was evidently a deficiency in the slackening off and oiling of the fishplates and fishbolts along this section of the line, compounded by “burring” of the fishplates. Colonel McMullen conducted a track inspection on 7th June when the weather was just as warm, during which slackening of the fishbolts caused the rails to “jump” and hitting the fishplates made them “jump” a second time, effectively closing the gap, proving that some of the joints were “frozen” and incapable of expansion. Careful examination of the fishplates and fishbolts revealed “bulges” at the fishbolt holes which prevented proper metal to metal contact between the plate and the rail and compromised the effectiveness of oiling in keeping the joint operable. Collectively these faults had resulted in a considerable length of track that was unable to absorb the heat of the sun without distorting, a problem that was compounded by some places having recently riddled ballast and others where the depth of ballast was insufficient to resist the lateral movement of the track.

Colonel McMullen considered that the passage of ‘The Flying Scotsman’ had provided the required thrust and vibration that exacerbated the undue compression in the rails and released the locked-up stress in the track. The principal cause was a deficiency of maintenance, exaggerated by the heat of the sun and ganger Barnaby, whose length this was, came in for criticism on this point, as did his superior, permanent way inspector Bailey, who had been reminded of hot weather precautions by the district engineer on 27th May. McMullen also censured guard Olney of the ‘Scotsman’ for failing to realise the seriousness of the vibration of his van and down-playing its significance instead of reporting it from a lineside ‘phone or at the next signal box. Colonel McMullen also had reservations about the use of automatic signals and the practice of switching out boxes, stating that if Tollerton signal box had been manned the accident might have been prevented. In the meantime, the trap was set and was simply waiting for the 12:15 Express to spring it…… which it duly did, much to the detriment of No. 60153!

Collision at Offord 7th September 1962 – No. 60123 H.A.Ivatt

Like many freight train accidents which involved no passengers or loss of life, there is no official record of the Offord collision so the following article has been assembled from newspaper and eye-witness reports of the accident.

On the night of 7th September 1962, a northbound 20:25hrs King’s Cross to Gateshead Express Goods was stopped at signals at Offord (between St. Neots and Huntingdon) when, at 22:15hrs the following 20:50hrs King’s Cross to Ardsley (Leeds) Express Goods, headed by Peppercorn Class A1 No. 60123 H.A.Ivatt, ran into the back of the stationary train. The A1 was derailed and fell onto its right-hand side, its bogie being torn off by the violence of the crash, and fifty or so wagons were variously damaged or derailed. All four running lines were blocked, the slow lines less so than the fast lines, and trains on the East Coast Main Line had to be diverted between Hitchin and Peterborough via Cambridge and Ely, adding some two hours to their journey times.

Four of the six crew were injured and taken to Huntingdon County Hospital, the most serious being John Theodore, the guard of the 20:25hrs Express, who sustained injuries to his head, leg, chest and pelvis and was later transferred to Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, described as “seriously ill”. The driver of No. 60123, Frederick Handley, was scalded although his condition was later described as “fairly satisfactory” whilst the other two, fireman of the 20:25hrs Express, L. Maynard, and the guard of the 20:50hrs train, Sydney Haywood, were later discharged.

Clearing up operations began promptly and, although some services were cancelled, priority was given to Anglo-Scottish trains to ensure these kept running. Three breakdown trains and the Peterborough crane attended the scene, re-railing as many wagons as possible and getting H.A.Ivatt back on the track. Gangs of men who had been working all night were provided with food from a restaurant car brought down from Grantham. The lines were all clear and back in operation by the evening of 8th September, less than 24 hours after the crash.

No. 60123 entered Doncaster Works on the 24th September but was withdrawn on 1st October, the first Peppercorn A1 to be condemned. By this date even minor faults could be sufficient to lead to a locomotive being scrapped and No. 60123 was extensively damaged. With a service life of just 13 years 7 months, H.A.Ivatt was one of the shortest-lived A1s and the only one unlucky enough to have been involved in two serious accidents, the first being the collision and derailment at Lincoln in October 1949 (see TCC 60). Scrapping was at Doncaster Works and the last reported sighting of No. 60123 was in the Works yard on 14th October.

All photos courtesy of the Transport Treasury

A general view of the crash site, with two breakdown cranes hard at work.

A pair of extensively damaged box vans lie at the trackside.

The Peterborough crane lifts another van from the tangle of wreckage.

No. 60123 H.A.Ivatt looking very sorry for itself.

A plate wagon has been inserted as a runner between the locomotive and its tender.

No. 60123’s bogie has been placed on the plate wagon. The entire consist would then be worked to Doncaster.

Collision at Otterington 16th January 1964 – No. 60120 Kittiwake

In the absence of any further information about this accident, we can but record it as a postscript to this short series of articles detailing accidents that befell Peppercorn A1s. No. 60120, Kittiwake, was withdrawn due to damage sustained in a collision with the rear of an up freight train stopped for examination at North Otterington (Nr. Northallerton) on the ECML in the early hours of 16th January 1964. The A1 was running south light engine at the time and this was the last serious accident to happen to an A1.

Epitaph – only hours after the collision, No. 60120 is seen at York – Richard Postill