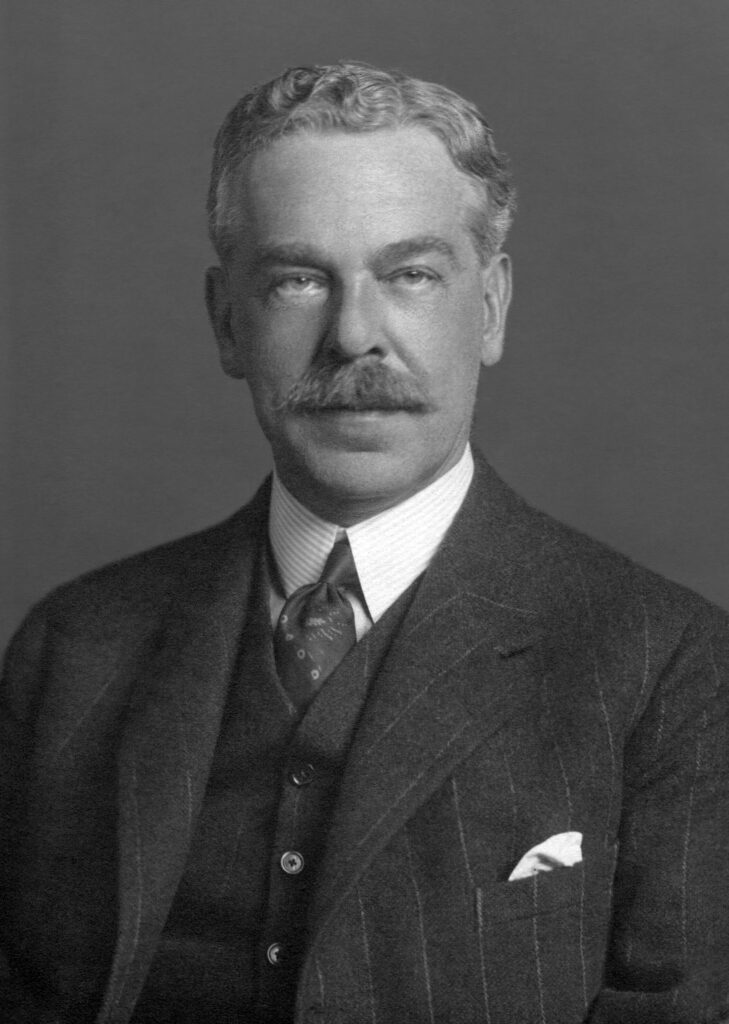

Sir (Herbert) Nigel Gresley (19th June 1876 – 5th April 1941) was one of Britain’s most famous steam locomotive engineers, who rose to become Chief Mechanical Engineer of the London and North Eastern Railway. He was the designer of some of the most famous steam locomotives in Britain, including the LNER Class A1 and LNER Class A4 4-6-2 Pacific engines. It was his A1 pacific, Flying Scotsman, that was the first steam locomotive officially recorded over 100mph in passenger service, and an A4, number 4468 Mallard, still holds the record for being the fastest steam locomotive in the world (126mph). Gresley’s engines were considered elegant, both aesthetically and mechanically.

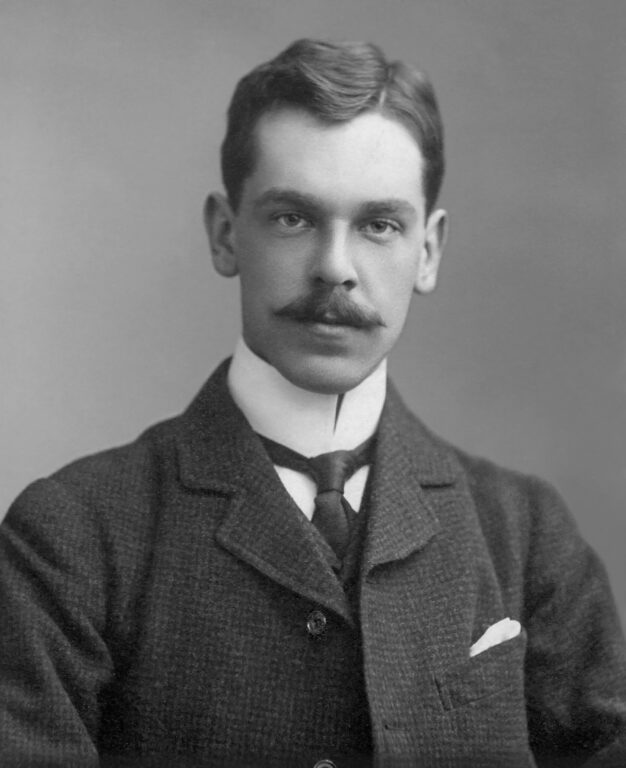

Gresley was born in Edinburgh and was raised in Netherseal, Derbyshire, a member of a family long seated at Gresley, Derbyshire. After attending school in Sussex and at Marlborough College, Gresley served his apprenticeship at the Crewe works of the London and North Western Railway, afterwards becoming a pupil under John Aspinall at Horwich of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. After several minor appointments with the L&YR he was made Outdoor Assistant in the Carriage and Wagon Department in 1901; in 1902 he was appointed Assistant Works Manager at Newton Heath depot, and Works Manager the following year.

This rapid rise in his career was maintained for, in 1904, he became Assistant Superintendent of the Carriage and Wagon Department of the L&YR. A year later, he moved to the Great Northern Railway as Carriage and Wagon Superintendent. He succeeded Henry A. Ivatt as CME of the GNR on 1st October 1911. At the 1923 Grouping, he was appointed CME of the newly formed LNER. In 1936, Gresley was awarded an honorary DSc by Manchester University and a knighthood by King Edward VIII; also in that year he presided over the IMechE.

During the 1930s, Sir Nigel Gresley lived at Salisbury Hall, near St. Albans in Hertfordshire. Gresley developed an interest in breeding wild birds and ducks in the moat; intriguingly, among the species were Mallard ducks. The Hall still exists today as a private residence and is adjacent to the de Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre, with its links to the design of the famous Mosquito aircraft during World War II.

Gresley’s long association with locomotive and rolling stock design provided him with ample scope for his abilities. His strong advocacy of three-cylinder, single-expansion propulsion was justified by its success on the LNER in the form of his own conjugated valve motion which he contended was preferable in terms of weight saving and ease of maintenance compared to having three separate sets of valve gear. However, the suitability of this valve gear did not prevent him from trying other forms of valve gear, as witnessed by the use of Lentz poppet valve gear on the D49 4-4-0s and, of course, Cock o’ the North. Never afraid to learn, comparative trials with Great Western engines persuaded him to adopt long-travel valves and his observations of Chapelon’s work was evidenced by the use of streamlined steam passages in his later designs.

Gresley was a great believer in the principle of the big boiler including, where possible, a wide firebox and large grate area. He also promoted the idea of a stationary testing plant for locomotives in the UK, a scheme he championed after the visit of No. 2001 to the Vitry testing plant in 1937; the results of the test on Cock o’ the North suggested that the locomotive could be further improved and some of these modifications were applied to subsequent members of the P2 class. Had the war not interrupted its construction, Gresley might have been able to witness further tests at the new Rugby facility.

The ever increasing speeds demanded by the traffic department led to 100mph runs being recorded by his Pacifics, culminating in Mallard’s world record of 126mph in 1938. In 1936, Gresley designed the 1,500V DC locomotives for the proposed electrification of the Woodhead Line between Manchester and Sheffield although the Second World War forced the postponement of the project, which was completed in the early 1950s. Other innovations introduced by Gresley included corridor tenders, the use of boosters, his double-bolster bogie, electric cooking on trains, the articulation of coaches and, in his final design, the class V4 locomotives, the use of a thermic syphon.

Gresley died after a short illness on 5th April 1941 and was buried in Netherseal, Derbyshire.